Purpose

Naturally evolved biological innovations could help solve many of humanity's most pressing challenges. However, our ability to discover them is bottlenecked. Only a small portion of the world’s biodiversity has been sampled, and even less has been characterized. Approaches that can identify useful biology at scale are needed. A comprehensive accounting of evolutionary history may be the key. Structuring biological data through an evolutionary lens enhances analytical capabilities, predictive power, and generative potential. It can also be our guide, telling us where in the tree of life we should look next. Here, we provide a framework for searching for bio-utility, outline aspects of biological variation that hint at utility, and discuss multiple ways to integrate evolution into the ongoing search for bio-utility.

Background

All organisms must address a multitude of challenges during their lives. Evolutionary innovations underpin organisms' ability to survive and contribute to Earth’s remarkable biodiversity. Bioprospecting approaches have aimed to leverage this diversity for human benefit. Food security and agriculture, manufacturing, and healthcare have all benefited immensely from the fruits of bioprospecting [1] [2]. However, there remain limits. Vast swaths of biodiversity remain unexplored and undescribed [3], and we lack frameworks to fully leverage the data that have been collected. Efficient, scalable, and strategic frameworks that help us better mine biological knowledge and generate novel predictions may have outsized potential.

Bioprospecting

A major goal of bioprospecting is the identification of commercially useful molecules (here described as molecules with “bio-utility”). A typical workflow may involve sampling and identification of organisms/molecules from different environments, thorough laboratory characterization, and potential translational application [1]. This strategy has yielded numerous discoveries, especially in therapeutics development [4] [5]. It also relies heavily on serendipity and, given its resource intensity and methodological challenges [1], is often hard to scale.

More recently, in silico bioprospecting has tried to address some of these challenges. Rather than relying on luck, in silico approaches attempt to leverage pre-existing large comparative datasets [1] [6] [7]. This strategy circumvents some of the high-risk, time-consuming steps of traditional bioprospecting, yielding some successes [7]. However, the heavy reliance of these methods on a priori use cases or target molecules means they struggle to help us learn more general patterns that may be key for scaling the search for bio-utility [7]. These approaches also assume that sufficient useful variation exists in current databases to empower universal prediction. There are reasons to be skeptical. Databases are taxonomically biased [8] and, in the biology they contain, power certain findings over others [9]. In reality, the breadth of biological variation that in silico approaches search is heavily constrained compared to the true landscape of molecular variation. This means that, like more traditional approaches, in silico bioprospecting also faces severe bottlenecks with respect to scaling and generalizability. So, what should be done?

Establishing an evolutionarily informed bioprospecting framework

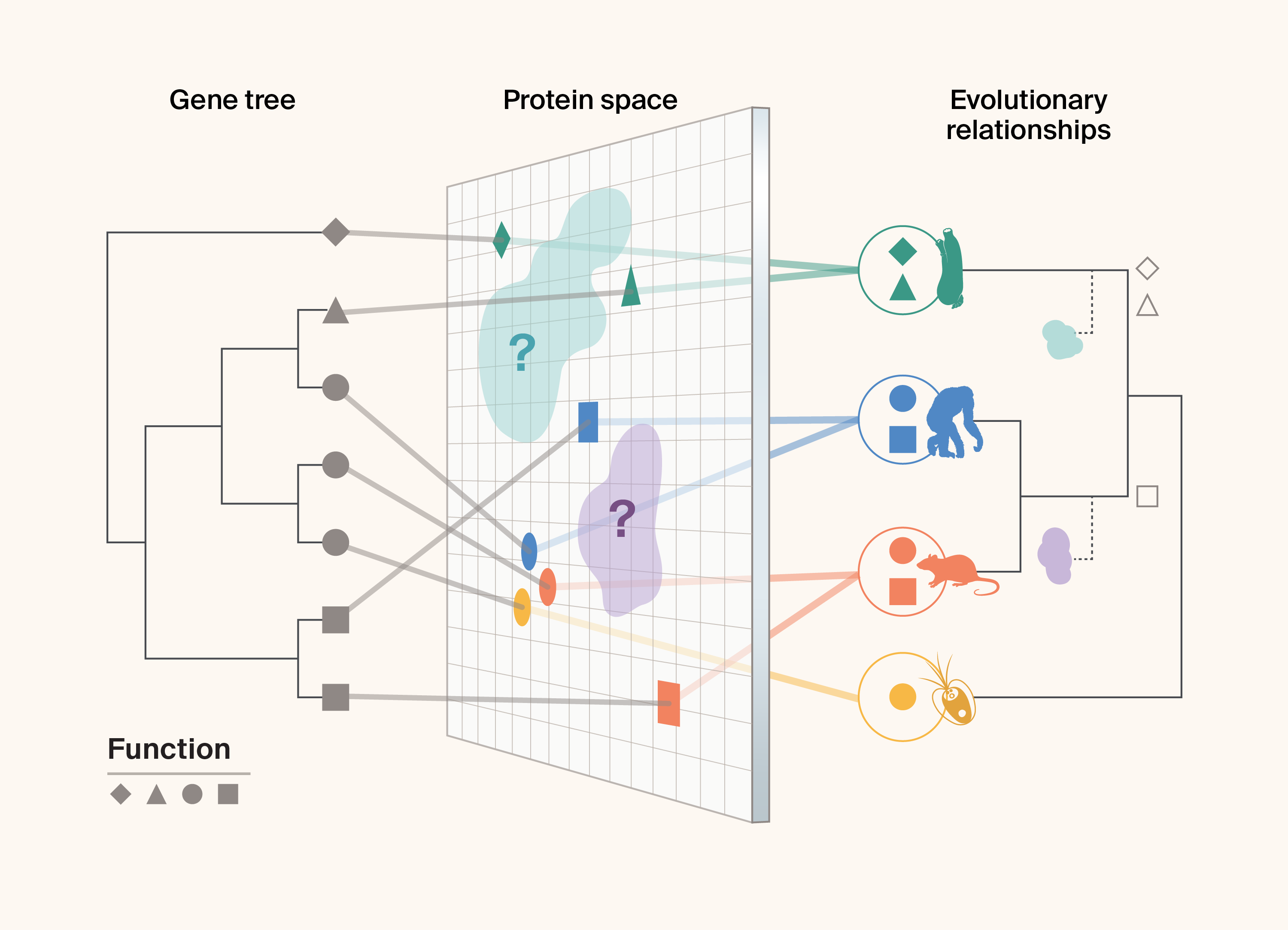

A scalable, evolutionarily informed framework to identify potential bio-utility is needed (Figure 1). In essence, such an approach combines the best bits of both traditional (increasing the breadth of sampling) and in silico bioprospecting (more deeply interrogating existing data). Here, we propose a framework that seeks to learn predictive evolutionary and biological features of bio-utility through iterative exploration and refinement.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the different data that can be integrated to search for bio-utility, i.e., whether proteins have interesting, useful, and leveragable characteristics, across a protein family.

Discrete sources of information about the protein family include the amino acid sequences of proteins which can be extracted from archived datasets and used to produce a gene tree representing the evolutionary relationships between proteins (left; different symbols represent different protein functions), a multi-dimensional plane representing “protein space” (in this case represented in 2D) which captures the integrated multidimensional variation of different protein features (including amino acid sequence, protein structure, and protein physicochemical properties, for example; middle; symbols represent protein functions and the distance between points represents the similarity in characteristics used to construct the surface). The right side of the figure shows the additional information gained by incorporating the evolutionary relationships between different species (exemplified here by a sea squirt, a chimp, a rat, and an algae) and the proteins that have evolved within them (which also allows us to determine whether, and to what extent, genealogies may differ between a given gene tree and the species tree). Unsampled areas of protein space, which future collection or in silico protein design efforts may wish to fill, are illustrated with “?,” with the species tree showing corresponding symbols illustrating lineages that, if sampled, might help us fill these gaps in protein space most efficiently.

Developing indicators of bio-utility

All attempts to bioprospect need an idea of what's useful. What are you looking for, and how will you know when you’ve found it? A priori knowledge of a desired function or feature is commonly used to narrow the search space to a manageable size. However, this approach isn’t always possible as scaling is often limited by what we already understand.

A more agnostic approach may attempt to uncover utility signatures directly from biological variation. Data are gathered that might form a close-to-comprehensive view of a biological system. From these, indicators of bio-utility may be statistically identified, highlighting the relevant parts of the system to focus on. The evolutionary distribution of these indicators may indicate where to prioritize further exploration. This deeper characterization may refine our bio-utility estimates (maybe further sampling uncovered a novel, undiscovered functional class), and so on, allowing iterative updates to what we consider useful.

What might an actual application of this look like? Proteins offer an ideal example. Proteins are molecular machines that exist at the interface of sequence-encoded information (DNA/RNA/amino acids) and the biophysical world of organismal function. Given this, attempts toward comprehensive characterization may be more tractable than other areas of biological organization. Broad components of a protein’s biology can be captured by accounting for its amino sequence, structure, and physicochemical properties [10]. By understanding how these scales interrelate across organisms, it might be possible to uncover generalizable signatures of protein biology.

Now, let’s imagine we have reduced the dimensionality of variation at each level across a whole protein family. For example, reducing the highly dimensional amino acid sequence data captured in a multiple sequence alignment to place proteins relative to one another onto a plane (for our purposes, we'll illustrate this as a two-dimensional flat surface), which we could refer to as an “amino acid surface” (Figure 2). Repeating this dimensionality reduction across scales, i.e., producing lower dimensionality representations of amino acid sequences, protein structures, protein physicochemical properties, and protein functions (all of which taken together represent the complete “protein space”), allows us to build a robust picture of the diversity of proteins within each protein family (as illustrated above in Figure 2). We can then interrogate patterns of variation across scales to effectively query the known protein landscape and to identify areas of each surface or complete “protein space” that are sparsely sampled (i.e., where we should direct future sampling efforts). Below, we outline three possible indicators that signal whether specific proteins within a protein family may exhibit bio-utility (Figure 2).

Figure 2. An interactive visual representation of three indicators of bio-utility.

Each indicator can be evaluated across proteins within a protein family by placing proteins on different planes that represent multidimensional variation at each level, and by investigating the arrangement and relative distances between proteins across levels (taken together, these planes represent the overall “protein space” shown in Figure 1). Links between surfaces highlight the relative location of the same protein across levels of biological organization, in this case from amino acid sequence, through to protein structural characteristics, physicochemical protein properties, and finally a categorical protein function. The code used to generate this figure gallery is available on GitHub (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.18489402).

Indicator 1: Extreme structure or properties

One signal that a protein may have bio-utility is that it sits at the limits of its family’s physical properties. These proteins may occupy novel portions of structural or functional space. Proteins could be identified as having putative bio-utility related to extreme properties if 1) they're within a certain distance to the edges of the observed protein surface or 2) they're identified as being distant from the mean values of the protein family.

Example: DNA polymerases from extremophiles have novel extreme thermostability

DNA polymerases synthesize chains of nucleotides according to a DNA template. While these enzymes are present broadly across the tree of life due to their foundational role in duplicating genetic material prior to mitotic cell division and DNA repair, their thermostability is highly variable. In extremophiles specifically, enzymes that carry out core functions must evolve extreme thermotolerance to avoid denaturation. The DNA polymerase present in the bacterial species Thermus aquaticus, which thrives in hot springs (also known as Taq polymerase), is thermally tolerant up to a remarkable 95 °C [11]. Although many DNA polymerases share similar properties, the extreme thermotolerance of Taq polymerase enabled its use in various biotechnology applications, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), where the ability to withstand cyclical heating and cooling is critical. On a theoretical protein surface capturing protein thermotolerance, extremophiles such as Taq are likely to define the bounds of the surface due to the strong selection to prevent protein denaturation, allowing them to be identified with indicator 1.

Indicator 2: Discrete function

A protein may have bio-utility if it performs a categorical function that other proteins in its family don't. This indicator could be calculated by considering variation across multiple levels. Proteins may have discrete bio-utility if they have a novel function (regardless of their similarity to proteins across other levels). We can increase the stringency of this indicator to find surprising functional novelty by requiring that proteins sit within a certain proximity to one another on other surfaces while having divergent functions.

Example: Different structurally similar S1A serine proteases have discrete functions

S1A serine proteases are enzymes that break down proteins [12]. This protein family is particularly interesting because related proteins (homologs), specifically paralogs that have evolved through gene duplications, have evolved remarkably different functions, cleaving peptides at different discrete residues, despite being very similar in sequence and structure. For example, trypsin has an S1 pocket that attracts positively charged side chains and cuts predominantly at arginine (Arg) and lysine (Lys) residues, while chymotrypsin has a hydrophobic S1 pocket and cuts at tyrosine residues (Tyr), and elastase has a restricted S1 pocket size and, as a result, cleaves at alanine (Ala) residues [13]. Their roles in development, digestion, and immunity have made S1A serine proteases and their inhibitors useful proteins in biotechnology [14]. This family of proteins could be identified using indicator 2 due to the combination of their proximity to one another on an amino acid surface (or protein structure surface) and their distance from one another on a protein physicochemical surface or protein functional surface.

Indicator 3: Conservation or convergence of function

Finally, a protein may have bio-utility if, despite being unlike other proteins across some levels of organization, it exhibits similar properties or functions across others. These proteins represent different solutions to similar biological problems, yielding similar emergent properties or functions through distinct sequences, structures, or mechanisms. This pattern can reflect either a conservation of protein properties, where non-essential aspects of sequences diverged across lineages while their core function remained the same, or from convergence, where lineages with different genetic backgrounds converged towards similar functional solutions over time, allowing them to solve similar problems. Proteins have putative bio-utility if they are distant from other proteins on some organizational levels (e.g., on an amino acid surface) but close to other proteins on other functional levels (e.g., on a protein physicochemical surface).

Example: Antifreeze proteins that have evolved across taxa serve similar functions despite being distantly related and structurally variable

Antifreeze proteins are specific polypeptides that have evolved independently across the tree of life to facilitate survival and minimize cellular damage at sub-freezing temperatures. Organisms have evolved proteins with a host of structures and mechanisms to achieve this, with the general mechanism being the inhibition of ice crystallization and growth by the binding of antifreeze proteins to small ice crystals as they start to form [15]. Antifreeze proteins have evolved in fishes [16] [17], insects [18], plants [19], and diatoms [20]. Antifreeze proteins from across the tree of life serve as interesting starting points for a host of biotechnological applications [21], including agriculture (crop thermal tolerance) and medicine (tissue preservation for transplants). These useful proteins could be identified using indicator 3 due to their highly divergent amino acid sequence and, in some cases, structure (resulting in large distances between proteins on an amino acid surface), but potential proximity on protein physicochemical and functional surfaces.

Integrating evolution to contextualize protein diversity

Leveraging the evolutionary history of proteins and the species in which they've evolved may empower the next generation of frameworks for identifying bio-utility. Evolutionary information can be leveraged to assess and mitigate the impact of our taxonomically biased sampling efforts, i.e., to better determine the proportion of the “true” diversity of proteins and taxa that we may have captured. Given that biological data continues to be collected [22] and described [3] at remarkable rates, replacing our reliance on serendipity with robust predictive frameworks is essential (Figure 1). Below, we outline three focal examples where integrating evolutionary can help us begin to iterate towards a predictive framework for identifying bio-utility.

Qn 1: What is the origin of a specific useful protein function?

Evolutionary information is critical to identifying the lineages in which specific protein functions evolved.

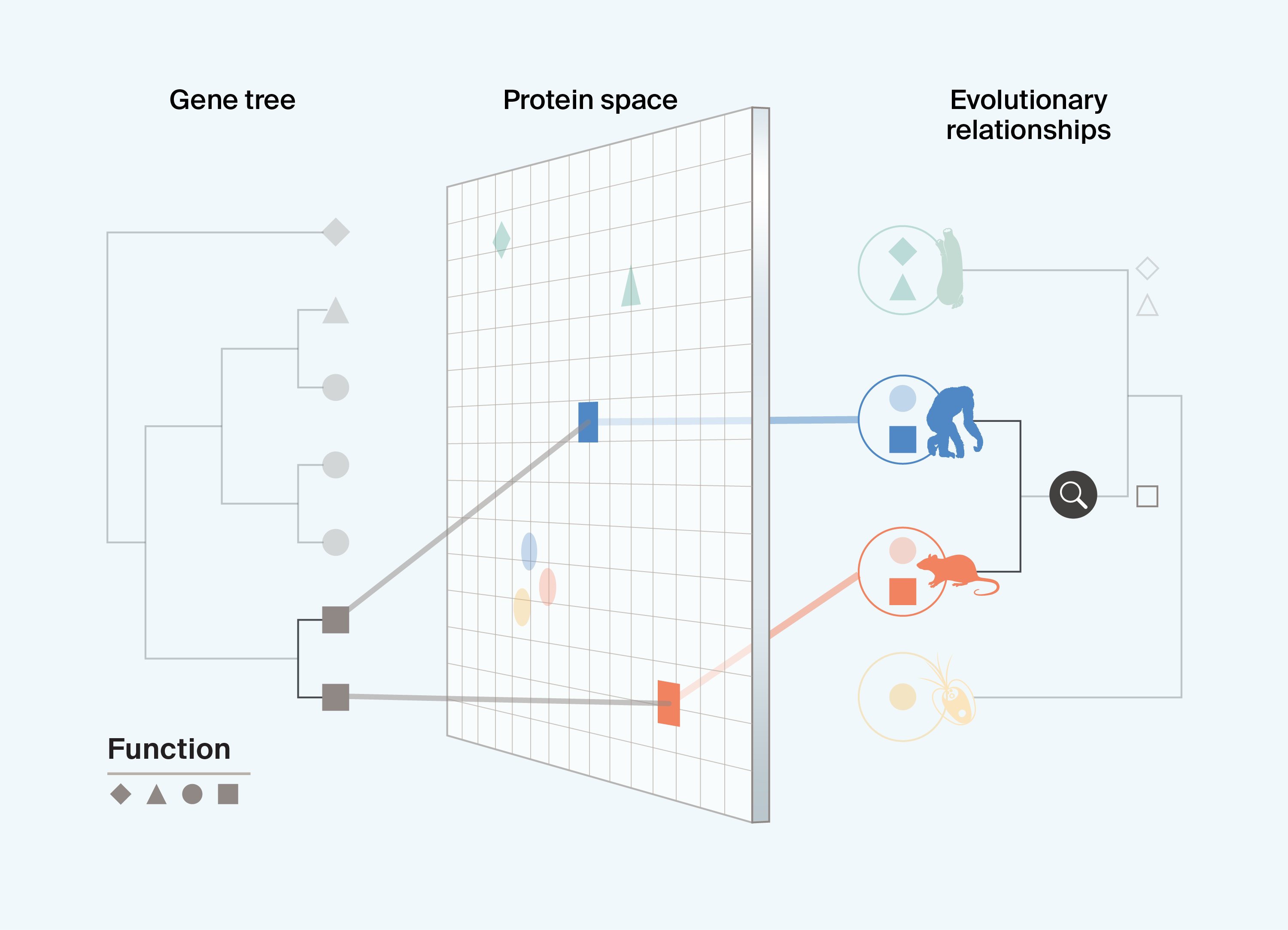

Investigating bio-utility in the absence of evolutionary information limits our ability to determine whether functional differences scale with, or are clustered by, relatedness. For example, knowing that the square protein function in Box 1 is present only in mammals (chimps and rats) helps us link protein variation to different gene pathways, phenotypic characteristics, and even selective pressures across these species. These patterns can help guide downstream applications. We may wish to identify only proteins with similar functions that have evolved in closely related taxa, as they are relevant to a target application (e.g., mammals may be suitable for human applications). In contrast, if we want to develop functionally similar but mechanistically distinct proteins that can be expressed in a distantly related laboratory species, we may select only proteins that exhibit bio-utility and have an ancient or distantly related ancestor.

Box 1. Identifying the origin of specific protein functions

Interpreting current data

Integrating protein information with evolutionary information can help us determine if, and when, functionally similar or useful proteins shared a common ancestor. It also allows us to find proteins that are more or less similar than the phylogeny predicts, and lineages in which protein diversification has occurred most rapidly.

Guiding future sampling

Understanding the origin of key protein functions helps us strategize future sampling to target unsampled proteins with specific functions in specific species or clades.

Qn 2: Are specific protein functions convergent or conserved?

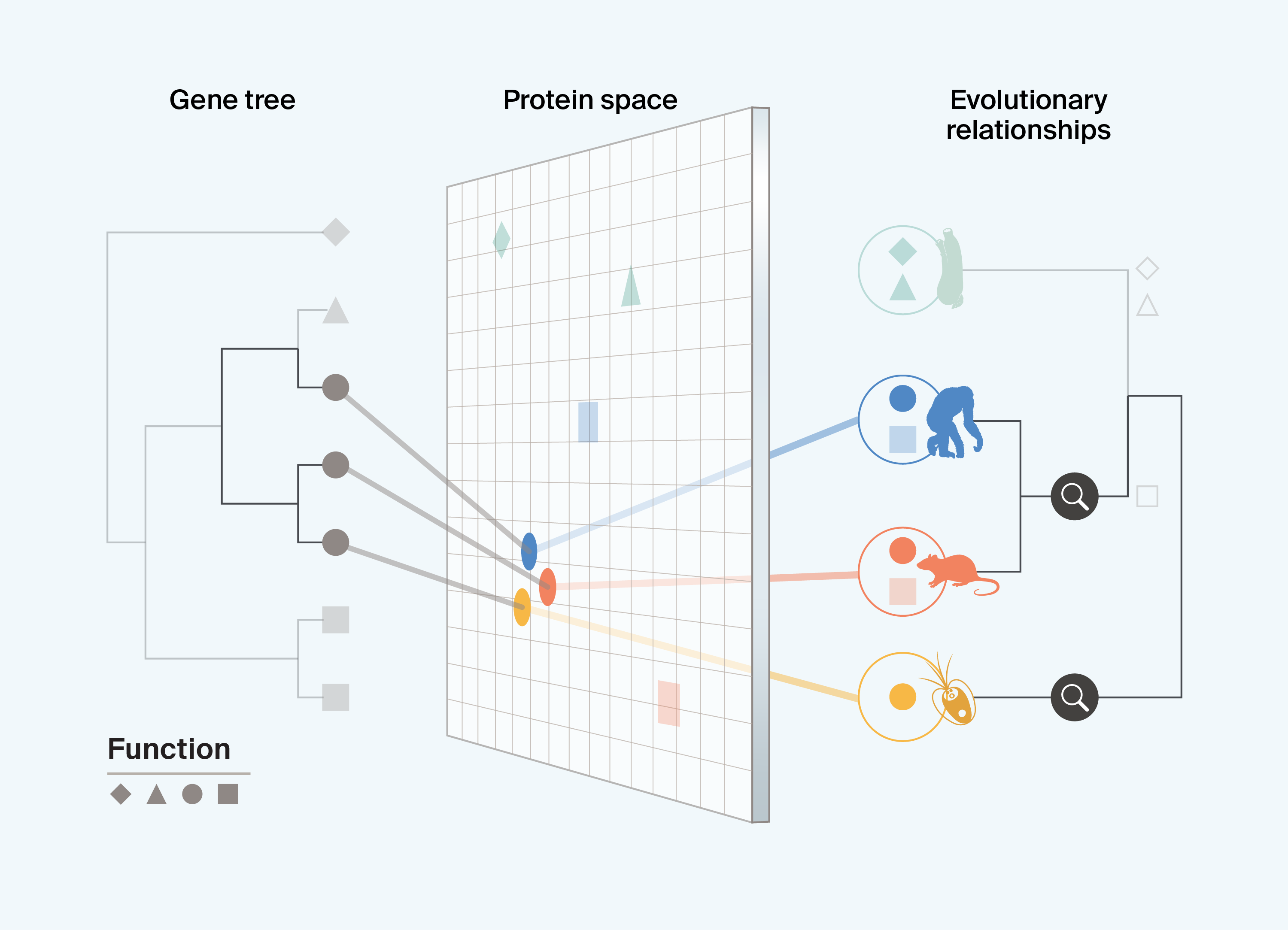

Evolutionary information can help us differentiate between proteins that have evolved similar functions through convergence versus conservation.

Proteins that exhibit bio-utility by exhibiting functional conservation or convergence can be identified using indicator 3, outlined above. While this indicator only makes use of protein information, i.e., whether two proteins’ functions are more similar than their amino acid sequences would suggest, protein information alone can't distinguish between cases of conservation or convergence.

For example, species-level relationships help resolve the fact that in Box 2, chimps, rats, and algae each have proteins with the circle function. Evolutionary information can help us begin to determine whether this function has independently evolved in algae or is conserved from a shared ancestor with the other species, guiding the downstream use of proteins with potential bio-utility. Cases of functional conservation are likely to have evolved in clades where, despite background sequence divergence amongst species, protein functions remain surprisingly similar. In contrast, cases of convergence reflect instances where different diverged lineages have proteins that have evolved to become functionally more similar to one another over time, despite having distinct evolutionary starting points. Proteins that have evolved through convergence (homoplasy) serve as interesting examples of functionally similar proteins that have evolved across distantly related lineages with variable genetic backgrounds. These examples hint at the theoretical bounds of different axes of variation (i.e., the range of amino acid sequences and protein structures) that can result in similar functions. In contrast, proteins that evolve similar functions through conservation (homology) hint at potential mechanistic limits for generating desired functions. These examples are important because it may be the case that, no matter how broadly we sample the tree of life, highly constrained functions will remain limited to specific lineages, with only a few starting points from which to iterate. They can also help direct our search for other proteins. If proteins have evolved through conservation, requiring specific sequence motifs or structures, then we could restrict our search for those proteins to lineages in which they have already evolved.

Box 2. Differentiating between protein function conservation and convergence

Interpreting current data

Integrating protein information with evolutionary information can help us determine whether instances of shared useful protein functions are the result of conservation or convergence. This helps us better understand evolutionary constraint on proteins with specific functions and the extent of protein variation that can result in functional similarity.

Guiding future sampling

Understanding constraint and convergence allows us to carry out targeted sampling of unsampled proteins more effectively and to assess cases where in silico protein design may be favored, in addition to helping establish useful starting points for protein design.

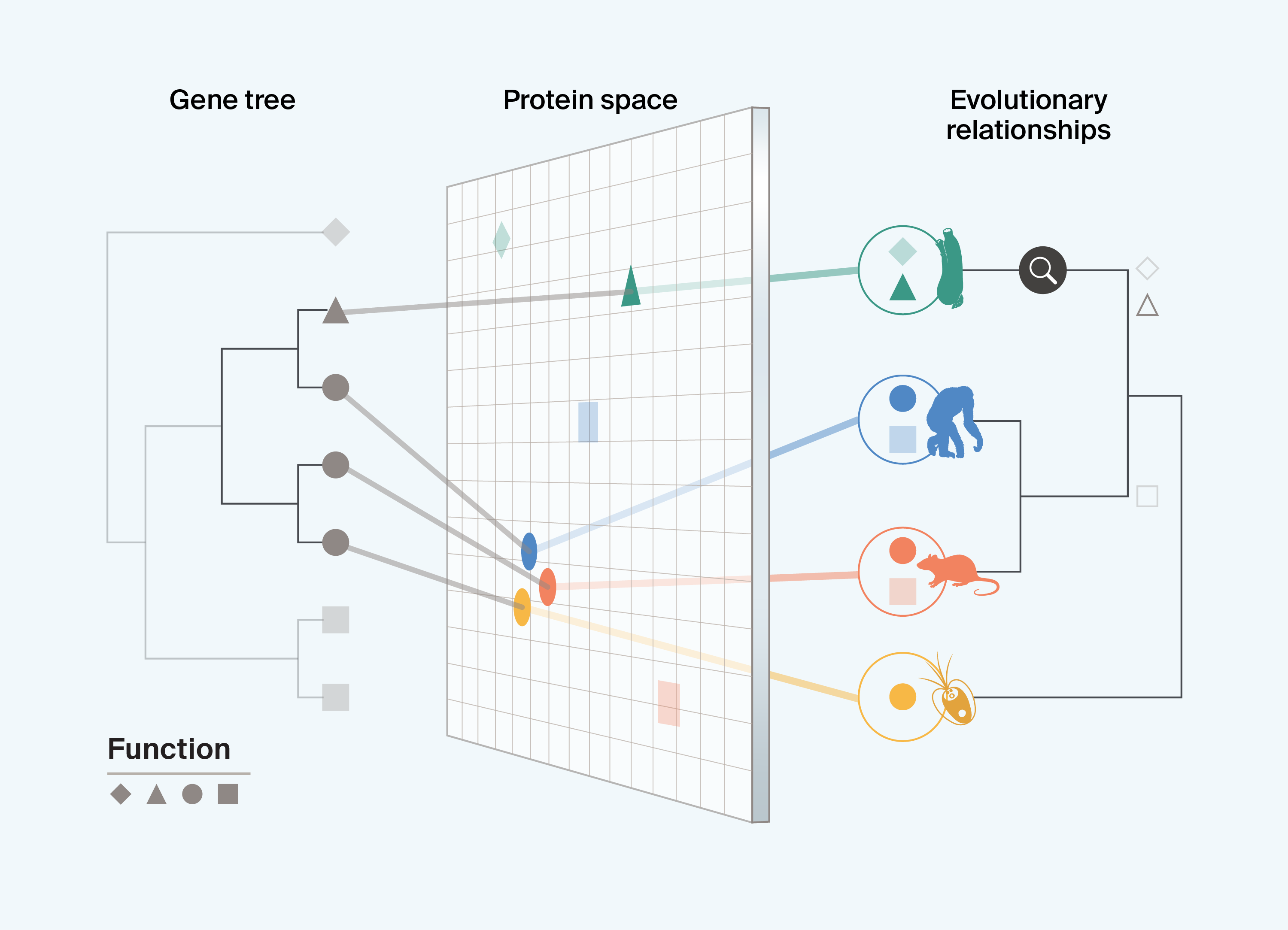

Qn 3: Is a specific, functionally novel protein an example of breakthrough novelty in the face of constraint?

Evolutionary information can help us identify proteins that have evolved novel functions in some species despite being constrained in others.

Using only protein information, it’s challenging to assess whether functionally novel proteins arose through strong selection or iterative change over vast macroevolutionary time scales. This information is best gleaned by pairing protein information with evolutionary information.

In Box 3, sea squirts are observed to have a protein with a novel triangle function. Adding evolutionary information allows us to assess whether sea squirts are enriched for functionally novel proteins due to their biology, or whether differences in protein function are proportional to their evolutionary divergence from other sampled taxa. Enrichment of novel proteins may occur as a result of specific lineages having strikingly different selective regimes to close relatives, and these species may serve as interesting focal taxa for identifying biological novelty. Some of the most valuable cases for developing new insights into protein biology may be those in which specific lineages have evolved proteins with novel functions, despite protein function being relatively constrained across other taxa. Combining the evolutionary history of proteins with that of the taxa in which they have evolved is critical for constructing predictive frameworks of bio-utility.

Box 3. Highlighting breakthrough protein novelty

Interpreting current data

Integrating protein information with evolutionary information is needed to highlight the evolution of functionally novel proteins that are usually constrained. These cases may arise through specific selection regimes and provide rare insights into how protein structure and function are linked and how specific protein characteristics may be essential for target applications.

Guiding future sampling

Understanding instances of breakthrough novelty will allow us to more broadly sample lineages that may be most likely to have evolved functionally novel proteins with untapped potential for biotechnological applications.

Conclusions

Here, we present an evolution-integrated bioprospecting framework to identify proteins with putative bio-utility in a scalable manner. We outline three discrete indicators of protein bio-utility and provide examples of how evolutionary information can be used to contextualise patterns of protein variation to better highlight and investigate useful targets. These indicators will help us identify proteins with putative bio-utility, i.e., those with extreme characteristics, striking functional differences, and those with conserved or convergent functions. Pairing protein and evolutionary information for proteins that are flagged as having putative bio-utility will subsequently allow us to build predictive frameworks that better capture the origins of functions of interest, instances of strong conservation or convergence across macroevolutionary timescales, and cases of breakthrough novelty. Together, this may be key to creating the next generation of methods for identifying novel bio-utility across the tree of life.

Pub preparation

We used Grammarly Business to suggest wording ideas and then chose which small phrases or sentence structure ideas to use.